A Day in the Life of an Observatory

A look into the diverse team of people who keep NOIRLab observatories running 24/7

26 April 2023

What do you imagine working at an observatory to be like? You may picture a lone astronomer sitting at the base of a telescope, pressed up against the eyepiece as they gaze out at the dark, starry sky. But the truth is the work extends far beyond that. It takes a large, dynamic team of people, with a diverse range of skills, working 24/7 to operate and maintain an observatory. And with the growing capabilities of remote-observing, the days of an astronomer even being present at a telescope are becoming rare.

NOIRLab hosts 70 of the most diverse and innovative ground-based telescopes in the world across three observing sites in Chile, Hawai‘i, and Arizona and employs around 500 full-time staff members.

Yes, the quiet hours of the night, when the cosmos opens itself up to exploration and discovery, are certainly an exciting time at an observatory. But those moments are only made possible by a wide range of teams collaborating throughout the day while the telescope isn’t conducting science. And though the clock never stops at an observatory, we will begin our journey at 8 a.m. when many daytime crew members start their day.

Esteban Parkes is the site manager at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO), a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab. Located in the Chilean Andes at an altitude of 2200 meters (7200 feet), CTIO is a complex of about 40 astronomical telescopes. As site manager, Parkes is responsible for overseeing the many teams that work for the observatory, including maintenance and facility crews, engineers, electricians, and more. To kick off each day, Parkes leads his crew through a communication meeting where they review the plan for the day and discuss updates of any critical projects that are underway. “We work during the day to have everything ready to do science at night,” said Parkes.

Parkes has been the CTIO site manager for about 10 years, but has been working on the mountain since 1986. With a background in electrical engineering, he started on the electronics team working on telescope instrumentation and integration. In the late ‘90s and early 2000s, he was a member of the development team for the 4.1-meter Southern Astrophysical Research (SOAR) Telescope located 10 kilometers (6 miles) southeast of CTIO on Cerro Pachón, and a short distance away from Gemini South. Now, he oversees the work of 20 staff members to ensure the observatories at CTIO are in the best possible condition for nighttime operations.

“At the beginning, I never thought I would have the level of responsibility I do now,” said Parkes, “It was a process of growing during all these years, and I feel very good with where I’m at now.”

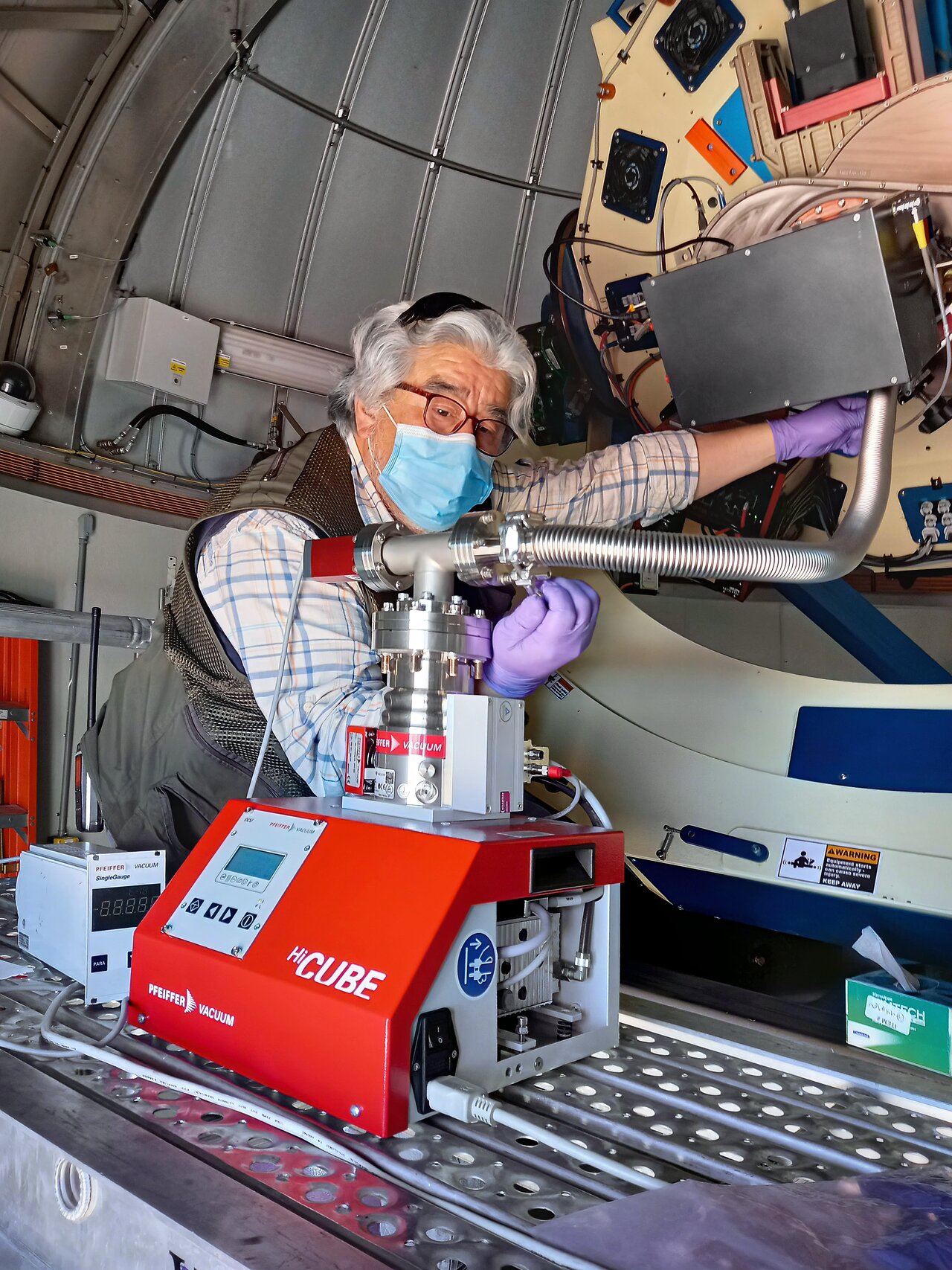

A key aspect of Parkes’s responsibilities is facilitating communications among his various teams. One of these is the engineering team — a vital resource as they build and enable upgrades to the telescopes’ instruments and infrastructure. “It can be a lot of pressure sometimes,” said Priscila Pires, mechanical engineer at CTIO, “because science cannot happen if the instruments or telescope enclosure have problems.”

Pires started working at CTIO in November 2021, bringing with her a background in both mechanical and systems engineering. From the small-scale components of an imaging sensor to the large-scale infrastructure that houses a telescope, Pires’s job is to provide high quality design and proper installation of the physical elements that make an observatory functional. “You never stop studying,” she said. “I need to learn how to work with optics, detectors, cooling systems; everything is new knowledge and I enjoy that a lot.” As an engineer, Pires works from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., and each day can bring something new and unexpected, so she must stay flexible. Even her working location can change at a moment’s notice.

We work during the day to have everything ready to do science at night.

Contrary to what may be expected, not all observatory work is conducted on site. In fact, Pires spends most of her days at her office in the coastal town of La Serena, Chile, located about 80 kilometers (50 miles) west of and about 2000 meters (6500 feet) lower than CTIO. But in the case of an instrument installation, upgrade, or malfunction, a trip to the summit may be called for. This type of work brings its own set of challenges, though, a significant one being the time constraints. “We need to plan everything that needs to be done during the day to finish by 4 p.m. because the telescope needs to be prepared for that night,” said Pires. “If you don’t finish, then you have to dismantle everything you did and come back the next day and try again.”

Indeed, the Universe waits for no one, so a major focus of daytime operations is on maintaining the telescope so that the upcoming night of observations achieves maximum scientific output. So while Pires concentrates on the instruments and infrastructure at CTIO, 10,000 kilometers (6213 miles) away in the early morning at Gemini North, one half of the International Gemini Observatory, operated by NSF’s NOIRLab, the daytime Science Operation Specialist (SOS) is making a comprehensive assessment of the many other tasks of observatory maintenance that need to be completed that day. “An SOS has much more of an overall picture of what's going on,” said Jennie Berghuis, SOS at Gemini North. “We can oftentimes find problems before they start because of that overall perspective.”

Science cannot happen if the instruments or telescope enclosure have problems.

As the daytime SOS, Berghuis works from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m from the Hilo Base Facility (HBF) in Hilo, Hawai‘i, about 45 kilometers (30 miles) east of Maunakea where Gemini North is located. Her main duty is to coordinate communication between the base and the mountain while ensuring the safety of both the people and the equipment. This means Berghuis relies on a broad knowledge base to not only monitor daily tasks, but also quickly and appropriately respond if problems arise. Whether it be optical equipment malfunctions, bugs in the software, or lapses in communication, Berghuis needs to know who to contact to remedy the issue. “SOSs are really good at being the glue between all the departments,” she said, “so learning how to collaborate with others is important.”

Berghuis also acts as a bridge between daytime and nighttime work, which officially transitions around 4 p.m. during astronomical twilight. In preparation for that transition, she performs quality assessments of the data collected the night before and checks that the telescope is properly calibrated for the upcoming night’s observations. These checks and assessments are crucial to achieving a smooth handoff from daytime to nighttime operations.

At sites in Arizona and Chile, where observers and telescope operators sleep on site during the day, the handoff from the daytime crew to the nighttime crew is an interesting part of the day. Around 4 p.m., while many are completing their duties for the day, a whole team of people are just waking up. And for those whose day is just beginning, the first priority is getting some food in their stomachs. This is where an essential aspect of observatory work comes in; the cafeteria.

“An army runs on its stomach,” said Dave Murray, Kitchen Supervisor at Kitt Peak National Observatory (KPNO), a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab, located 90 kilometers (56 miles) southwest of Tucson, Arizona, on the Tohono O’odham Nation. Murray, who has been working at KPNO since 1990 when he began as a dishwasher, works with his crew of four other cooks to make sure that KPNO staff have access to delicious, freshly-made food every day. Around midday, they serve lunch for the daytime workers, which includes scientists, facility and maintenance people, and staff at the Kitt Peak Visitor Center. And at 4:30 p.m., they transition to dinner service where they serve astronomers and telescope operators who have just emerged from their dormitories.

Over the decades, as remote observing has become more accessible, the physical presence of people at KPNO has slowly decreased. But, Murray expresses his continued joy of providing food for anyone who finds themself on the remote sky island that is Kitt Peak. “The best part is making people happy throughout the day,” he said. “Just having a warm meal and getting to sit down and talk, it's a relaxing atmosphere that people look forward to.”

Once the Sun has set — around 5 p.m. in winter and 7 p.m. in summer — the daytime crews head home and telescope domes begin to open in anticipation of that night’s observations. Nighttime operation at an observatory may look very different from what one would expect. Interestingly, it’s becoming rare for an astronomer to actually operate a telescope, or even be present during data collection. Instead, they submit proposals to a telescope detailing the exact observation they need — the location of the object, the time to observe it, and the conditions under which data can be collected, among other constraints. Then, a team of highly skilled telescope operators and observers collect the data for the astronomer. This requires extensive planning beforehand as well the ability to adapt in the moment to unforeseen complications.

It may sound weird, but the times when I have the most fun are when things go wrong.

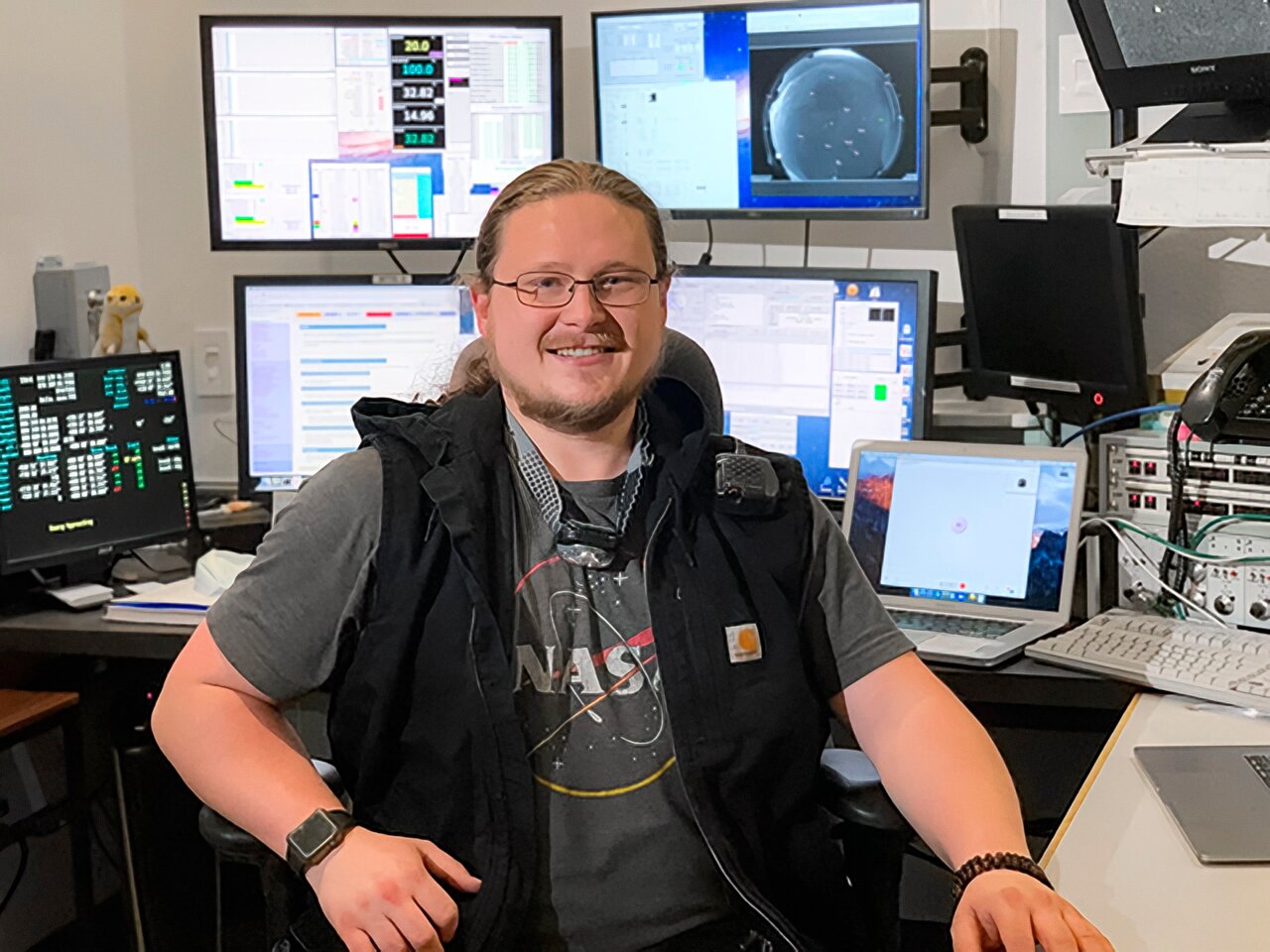

Every telescope operates slightly differently at night, but typically there is one operator and one observer present. At the WIYN 3.5-meter Telescope at KPNO, Thaxton Smith performs the duties of telescope operator. Because of the unique requirements of his job, he works in shifts of six nights on and nine nights off. On the first day of his shift, Smith arrives at the mountain at about 2 p.m. and sets up his sleeping quarters where he’ll rest each day from about 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. “It’s very rare that I’ll actually see any of the people who make the mountain operate,” he said, “but I love the night shift.”

A telescope is essentially a piece of heavy machinery, so as operator of WIYN, Smith uses his specialized training to make the machine run at its safest and most efficient capacity. He receives commands from the observer about where to point to the telescope and then executes those commands from his computer in the control room. And not only is he trained in operating the telescope, but he’s also trained in how to troubleshoot it. “It may sound weird, but the times when I have the most fun are when things go wrong,” he said. “It’s a chance to use all of the skills I’ve acquired to really feel like I’m making an impact in terms of salvaging a night.” When problems arise, Smith must be prepared to do a first-order investigation and either solve the problem or communicate the issue to someone who can fix it. Depending on the diagnosis, it’s up to the observer to decide how the night will proceed.

Though a schedule has been set beforehand outlining what observations to make and in what order, in the case of unforeseen hiccups or unexpected shifts in the weather the observer needs to think quickly to devise a new plan. “It's all about adapting and being as efficient as possible,” said Brittney Cooper, queue observer at Gemini North, “because we’re really trying to maximize the science output of the night.”

For Cooper, a night shift runs roughly from 5 p.m. to 5 a.m., and the observing queue for one night could have anywhere from 10 to 60 target objects depending on the conditions of the night sky and how long each observation will take. If an observation is facing challenges, Cooper may decide to move on to another one in the queue based on which observations have higher priority, the instrument that needs to be used, or whether an astronomical event is occurring at a specific time that can’t be missed. “It's a little stressful because these are people’s data,” she said, “and someone’s whole thesis could depend on if you get it or not, so the pressure is definitely there.”

Despite the unpredictable, and occasionally stressful, parts of their jobs, Smith and Cooper both agree that being a part of the scientific discovery process is incredibly rewarding. And every person involved in keeping an observatory running is a key part of that process, too. As Cooper so succinctly put it, “It takes a village.” And just as the Universe is an amalgamation of matter and energy all relating to each other, an observatory is a fluid network of people and operations that are all interconnected.

Links