ANTARES: More than just a stellar concept

NOIRLab’s Tom Matheson reveals the game-changing alert system that will make short work of pinpointing interesting cosmic activity

Profile

Facility Profile

Name:

-

The Arizona-NOIRLab Temporal Analysis and Response to Events System (ANTARES)

Target objects:

-

Transients, such as gamma-ray bursts, supernovae and novae

Processes data for:

-

Zwicky Transient Facility, operated by Palomar Observatory (currently) and Legacy Survey of Space and Time, operated by Vera C. Rubin Observatory (future)

Activation date:

-

June 2020 (v1.0)

Notable features:

-

Annotates, ranks, stores, characterizes and distributes alerts; can be tuned to find the “rarest of the rare” transients

8 June 2021

In his spare time, Tom Matheson likes to photograph the wildlife around him. Like many of NOIRLab’s astronomers, Matheson lives in Arizona, just a stone’s throw from the desert scrub, mountains and all kinds of lizards, hummingbirds and coyotes.

“I live on the outskirts of town, and I have been sitting here in my office at home looking out of my window, and I can see coyotes and javelinas and bobcats. So I like to photograph the wildlife that is all around us,” he says.

Matheson finds many analogs between being an astronomer and being a photographer. This can be in the sense that both involve optics, whether they be the optics of a telescope or a camera lens. It also relates to how both are now digitized, whether it’s an image from Gemini Observatory, or a wildlife snap on a digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) camera — there’s cross-pollination of the knowledge required for how to process both types of images.

When it finds a target of interest, ANTARES sends alerts to astronomers using the communication platform Slack, as well as via email, web hooks or cellphone Short Message Service (SMS).

It’s fitting then that Matheson’s day job involves looking at ways to get the best out of telescopic images of the night sky. The wildlife behaviour he’s looking for in this regard isn’t the nocturnal activities of coyotes and lizards, but transients — objects in the night sky that seem to change, be that in luminosity or position. This is how astronomers search for all kinds of cosmic activity, from exploding stars to active black holes.

Go back 20 or 30 years and the discovery of transients was relatively low-tech, often relying on an astronomer’s spotting something by eye. “Back when I was in grad school in the nineties, somebody would see something, and they would call somebody up at a telescope, and the rate was like one or two things [discovered] per night,” says Matheson. He tells the amusing story of how early gamma-ray burst researchers would sleep with their phones on their head, so that if it rang with an alert they wouldn’t miss it.

Fortunately, things have developed substantially since then. With the development of sensitive all-sky cameras, such as that on Palomar’s Samuel Oschin Telescope that comprises the Zwicky Transient Facility, and the upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory with its 8.4-meter Simonyi Survey Telescope in Chile, the numbers of transients being discovered and observed on a nightly basis is about to go through the roof, potentially millions of them being seen each night. This causes a problem because follow-up time on other telescopes is limited, and many transients could end up being lost in the data archives.

...early gamma-ray burst researchers would sleep with their phones on their head, so that if it rang with an alert they wouldn’t miss it.

To better appreciate this celestial wildlife, Matheson and his colleagues have developed the Arizona–NOIRLab Temporal Analysis and Response to Events System, or ANTARES for short. It’s a software tool designed to sort through all the transients discovered each night, flagging the most interesting for follow-up observations.

The system can work directly with the Target and Observation Manager (TOM) Toolkit, developed by software engineers at Las Cumbres Observatory. The open-access software enables astronomers to build a TOM system of their own, customizing it for their science so that they are able to prioritize targets and manage observations and data. Meanwhile, NOIRLab’s Community Science and Data Center (CSDC) supports ANTARES through the development of Time Domain Services.

“This is a project that we — meaning the scientists here at NOIRLab — had been wanting to build for quite some time, because we knew that when Rubin Observatory starts observing, there is going to be this tremendous flow of astronomical alerts.”

ANTARES currently works with the Zwicky Transient Facility at Palomar Observatory’s Schmidt telescope but Rubin Observatory will provide an alert stream 100 times bigger as part of the Legacy Survey of Space and Time.

Survey observatories like Palomar and Rubin operate by taking images of large areas of the sky. A reference image is then subtracted from these images. Anything that appears the same — in other words, is still the same brightness, or which hasn’t moved — goes away after the subtraction, while anything that remains is some astronomical object that has changed.

“We needed to find a way to automatically sort through all that data and decide which are the things that might be worth investing more effort to learn about, and so that’s what ANTARES does,” says Matheson.

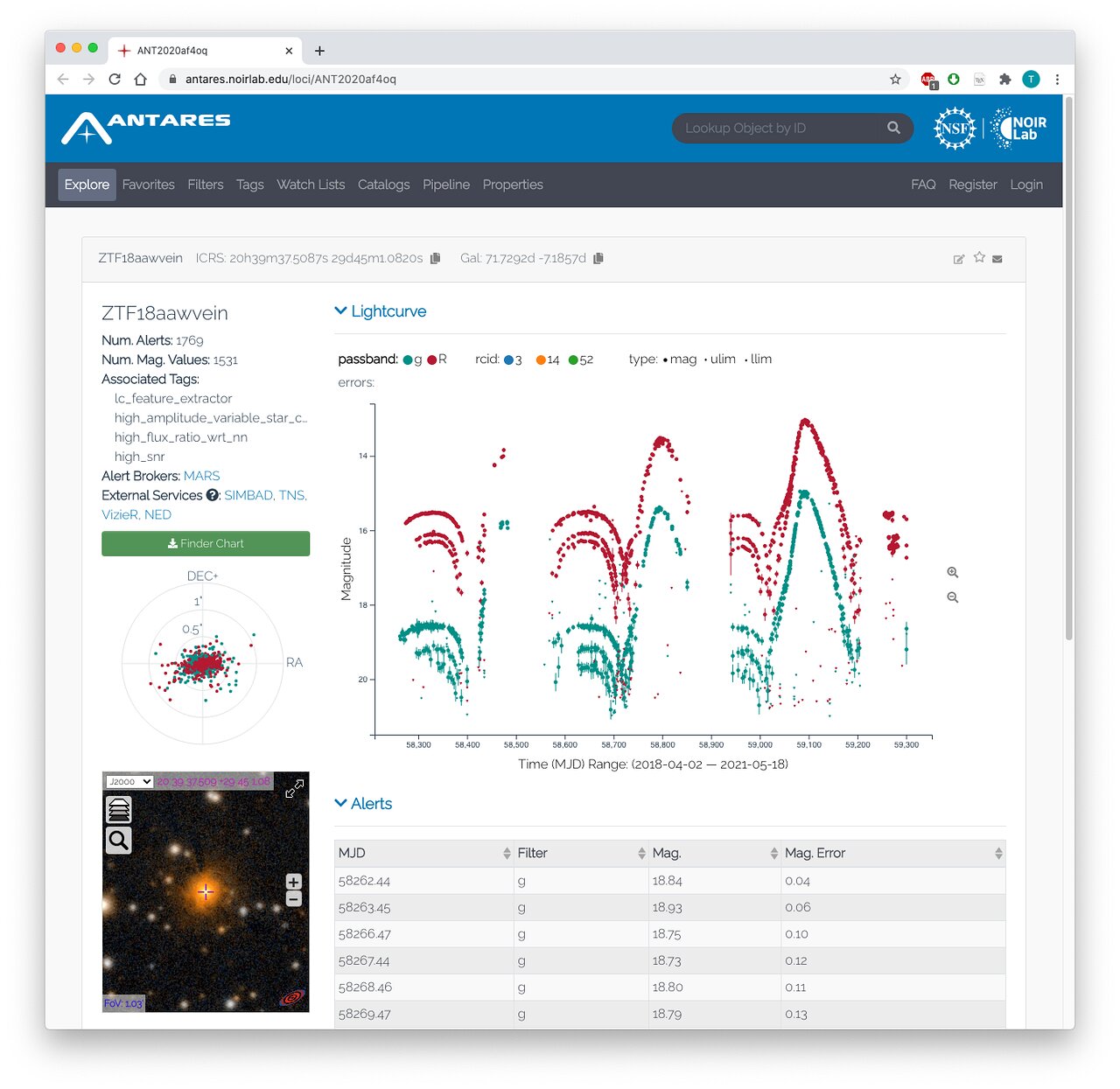

ANTARES applies filters to the transient data to narrow down which objects are of most interest. Is the transient near or in a distant galaxy? If the latter, what kind of galaxy and how far away? Is it in the galactic plane? By how much did its brightness change? Has it had an outburst before? The filters can refer to astronomical catalogs of galaxies and known variable stars, and can characterize the transients in real time. If an astronomer is interested in a particular type of object, they can specify certain filters to put the data through. Once ANTARES figures out what any given transient may be, it sends an alert to astronomers and observatories that may be interested in following up telescopically, and also adds the transient to watch lists.

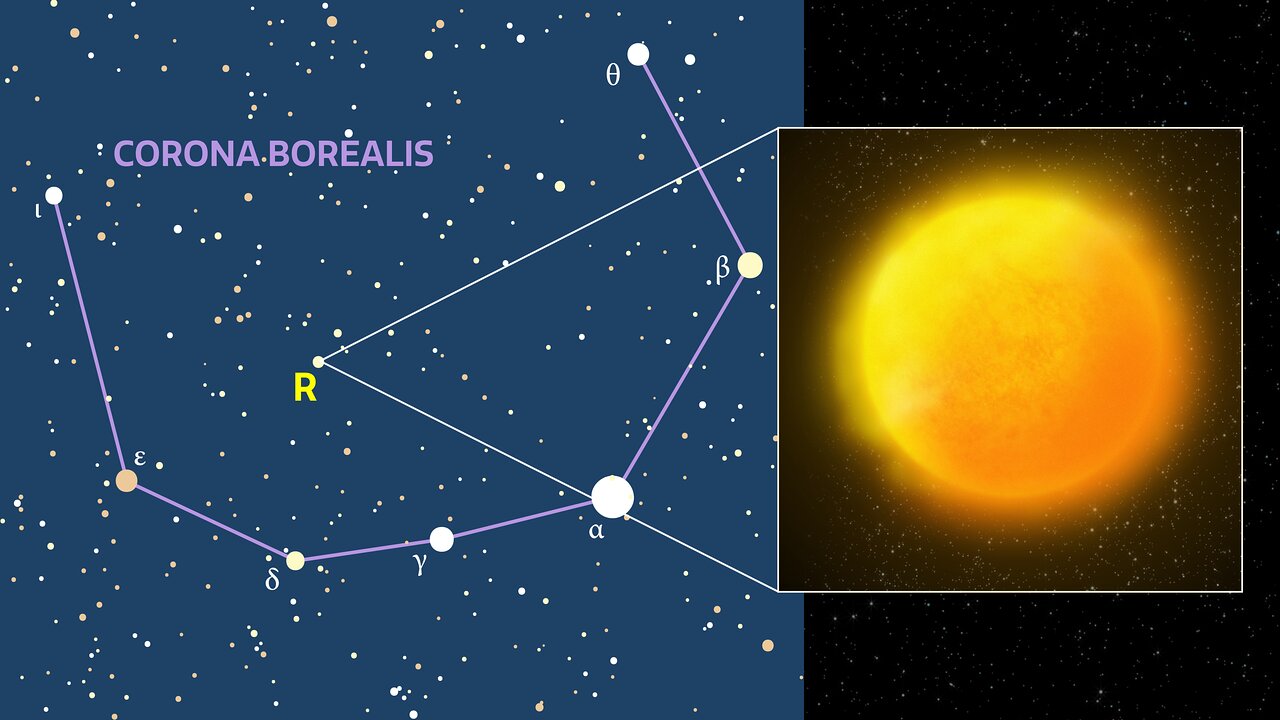

Matheson gives an example of how a fellow astronomer at NOIRLab, Chien-Hsiu Lee, used the ANTARES system to discover a rare type of variable star called an R Coronae Borealis star, named after a member of the constellation Corona Borealis, which is the archetype of this kind of star. It’s a yellow supergiant that is occasionally seen to dim dramatically for several months as a cloud of carbon dust blocks some of the starlight. So, in this case, the transient is notable for getting dimmer, not brighter.

ANTARES’s system of filters allowed the new R Coronae Borealis star to be identified and tracked through various other astronomical catalogs that may have recorded it, and showed that it was also a bright infrared source — typical of stars surrounded by large dust clouds.

“We were able to find all this out because ANTARES automatically told us; we didn't have to go look that up on our own,” says Matheson. It makes the study of transient objects so much more accessible to scientists and students all across the world — Matheson refers to it as the democratization of the time domain (time domain being the field of astronomy that looks for objects that change over time, i.e., transients).

This is a project that we had been wanting to build for quite some time… we knew that when Rubin Observatory starts observing, there is going to be this tremendous flow of astronomical alerts.

Although ANTARES allows astronomers to work more independently, the development of the system was anything but an independent process. Matheson and his fellow astronomers had to work with software developers and computer scientists to create ANTARES, and this cross-disciplinary approach was both hugely enjoyable and educational, he says.

"We started by working with computer scientists at the University of Arizona, and it was eye-opening, because we had to learn a completely different language to talk to each other. It was the same thing with our software developers. How they would think about implementing ideas is different from how we [astronomers] would think of implementing those ideas. And so, to be able to learn how things work across this whole, multi-disciplinary problem has been the most enjoyable part."

Links